MINDEN, ONT.—Like the lights on a runway guiding airplanes safely down, candles line the side of the road leading up to the sliding glass and metal doors.

A crowd of nearly 100 people mills about on the pavement as the hour nears midnight, some chatting, some singing, some holding candles, all here to mark the same thing.

It is a goodbye of sorts, a collective farewell, almost a wake. But it is also a gesture of thanks, from a community that has been coming to this site for the better part of three decades, with scrapes, bruises, broken bones and matters of life and death.

Singing “This Little Light of Mine,” these residents are here to say goodbye to the Minden emergency department, a wing of this small cottage-country hospital that has seen them through some of their darkest days.

There’s Helen Trinka, who believes she would not be here today if it hadn’t been for Dr. Bruno Helt stabilizing her failing kidneys and rushing her to the ICU in Peterborough.

There’s Cathy Arbour, who found refuge in the kind and caring arms of the Minden ED nurses and doctors after her 22-year-old son died unexpectedly in his sleep.

There’s Patrick Porzuczek, organizer of this night’s candlelight vigil, whose six-year-old daughter, Kinsely, was stabilized by Minden ED doctors after she suffered a severe heart arrhythmia during a dance recital.

Everyone here is alive today, or knows someone who is, because of the doctors and nurses who have spent the past 27 years making this ED an anchor of the community. They’re sharing memories Wednesday night of the friendly staff who knew most patients by their first names when they walked in; of the wall of fish hooks inside the ED, and the humorous record of mini-surgeries correcting cottage mishaps; and of the time Drs. David and Doug Fiddler, twins who started the ED 27 years ago, held fiddles and posed for a photo on the roof of the old hospital building for a charity calendar.

Finally, at midnight, with the moon shining down, the ED’s sliding doors, pasted with thank-you cards, slide open and shut for the last time as the doctors and nurses coming off shift enter the mass of thanks and gratitude — a gesture to end what has been a furious effort to save the site.

It’s an outcome nobody here wanted, and one that underscores fears about the future of small-town emergency medical services in a health-care system facing unprecedented pressures across the province.

‘Rural emergency medicine is tough’

Like many Ontario cottage country towns, Minden spent the spring bracing for tourist season, when its local population of 7,000 swells to more than three times that over the summer months, according to the mayor, as city dwellers flock to the nearby idyllic wilderness. With the influx comes an inevitable increase in mishaps needing medical care, on top of the steady health demands of the local population, which has a median age approaching 60.

The Minden ED was up to the task, says Dr. Dennis Fiddler, who has spent the past seven years working at the facility along with a small group of other doctors. Minden’s staffing is unique: physicians from surrounding-area hospitals, such as Peterborough, Lindsay and Barrie, leave their home hospitals to take on 24-hour shifts. Almost every physician shift had coverage this summer, Fiddler says, with just a few to be covered through Health Force Ontario, a type of job board run by the government that connects doctors with shifts across the province.

Unlike EDs that are part of larger hospitals, the Minden site (about two and a half hours north of Toronto) is stand-alone, which means it can be hard to attract staff, he says.

“Rural emergency medicine is tough. You have to rely on excellent clinical skills and collaborative teams because in rural areas, you are limited with what you have on hand,” Fiddler says.

“We do not have all of the advanced medical equipment of the city hospitals, but we provide the utmost care with the resources we do have. For this reason many medical graduates, be it nurses or physicians, do not want to work in these areas because it is very challenging without everything at your fingertips. To me, this is what I like about rural emergency medicine in Minden. The challenge of thinking on your feet, with the materials you have at hand.”

And the local residents, it seems, like it that way too. When Fiddler’s father Dr. David Fiddler, and David’s twin brother Dr. Doug Fiddler, set up the ED nearly 30 years ago, it was the community that ponied up the donations to buy most of the supplies and equipment. The Fiddler brothers are spoken of by residents with a kind of reverence.

It was David Fiddler, who, in 1995, upon learning that the Minden ED was facing closure due to a physician shortage, recruited his brother Doug, and seven other emergency doctors, to travel from their home hospitals to cover shifts in Minden. Such were his powers of persuasion that he managed to convince five chiefs of emergency medicine at other hospitals to make the trips to Minden to keep the ED going. Doug is now retired, and David died in 2014.

“It is true that my father and uncle were keystones here for many years. However, that shouldn’t take away from all of the other physicians that have worked here over the years,” says Dennis, who remembers studying in the back lunch room of the old hospital building as a boy while his Dad saw patients out front.

“All of them will tell you that this is a grassroots organization here at the Minden ED. Most of the physicians would say that all of the staff here, be it nurses, housekeeping, radiation technologists and clerical staff, are like family.”

Fiddler says he was surprised as anyone when on April 20 the local hospital board, Haliburton Highlands Health Services (HHHS), announced that it planned to “consolidate” the Minden ED with the Haliburton ED on June 1 — just six weeks away.

While separate sites, the Minden and Haliburton EDs are part of the same hospital, essentially two campuses of the same corporation. As such, HHHS argues the closure of the Minden ED isn’t actually a closure, but rather a move to combine services in the larger Haliburton ED, which is a hilly, winding 25-minute drive (on a good day, the locals will tell you) northeast of Minden.

Premier Doug Ford said last month that the Minden hospital itself is going to “stay open.” On Thursday, the hospital board began the process of removing the “H” from the side of the building and from nearby road signs. (HHHS says the residents will still be able to access physiotherapy, bone densitometry and outpatient X-ray services by appointment at the Minden site.)

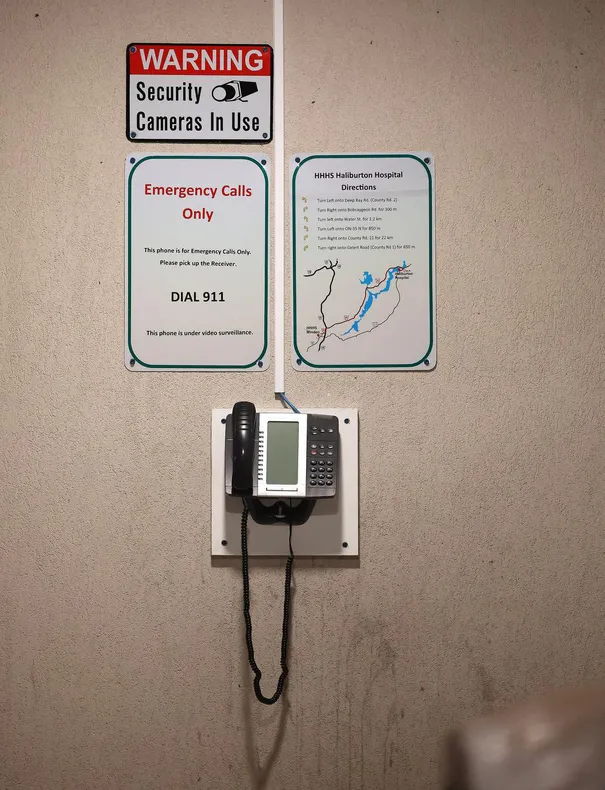

A phone for calling 911 was recently installed on the wall beside the ED’s now-closed sliding glass doors.

“It’s one of those jaw-dropping moments you need to absorb before you can react,” says Minden Hills Mayor Bob Carter, describing how he felt when he learned of the closure. “When it’s totally unexpected, you have no sense that it was coming and you just couldn’t figure out where it came from.”

The community was in shock.

“Here was an emergency room that was fully staffed for the summer, with the exception of three shifts per month because one of the doctors was taking semi-retirement, but was otherwise ready to go,” says Deputy Mayor Lisa Schell, who was born and raised in Minden and like many of her fellow residents, lives within a stone’s throw of the ED. “If the board of directors came to you and said this is what we are proposing and you don’t have a plan, you have nothing in place and you want to do it in six weeks, there isn’t a business owner in the world that would say ‘Yeah, that sounds like a good idea.’

“And at the end of the day, we’re not talking about money, we’re talking about the wellbeing of our community.”

Angered by the lack of warning and seeming lack of rationale, the citizenry rallied, forming a group called “Save Minden ER” that gathered more than 27,000 signatures for a petition urging a moratorium that was presented to the legislature. They printed more than 1,200 lawn signs, and erected two massive signs along highways 35 and 118 to warn cottagers of the impending closure.

The group organized a rally May 21, attended by close to 1,000 residents, as well as NDP MPPs Chris Glover and Jennifer French, and Liberal MPPs Adil Shamji and Stephanie Bowman. The community raised $87,000 for a legal challenge seeking an injunction and a judicial review of the decision. It proved untenable due to a lack of applicable legislation and case law.

Debbie Sherwin, a trustee of the campaign account, is in the process of reimbursing every donor. Some donations were in the thousands. Some were a few dollars.

Local resident Richard Bradley chokes up as he holds up a toonie and recounts one moment at the rally when an elderly woman using a walker came up to the donation table to ask if she had to pay to get in. Told that admission was free, she dropped a toonie into the donation jar.

“It hit me that night,” Bradley says. “This little lady had two dollars and that’s what she could spare out of her change purse. To me, that means so much more than somebody who’s sitting on a huge bank account that says, yeah I can do a thousand,” he says. “That toonie was worth a million dollars to that lady. So I went back the next day and bought the actual toonie she gave. I went and did a two-dollar transfer from my account into the campaign account. That’s how much this ED matters to people.”

Bradley keeps the toonie in his wallet and says he will never spend it.

HHHS has described the “consolidation” of Minden as a necessary step due to a “significant number” of near-closures at the Haliburton hospital, as well as nursing shortages at both sites; the difficulty in recruiting nurses generally due to shortages globally; existing staff being “stretched beyond limits” while constantly “fighting fires”; and worries that the county would be left with no ED at all if the Haliburton site had to close.

In the legislature in April, Health Minister Sylvia Jones said this is not a conversation about funding, but rather one “based on the needs of the community and appreciating that they want to best serve the community, and they’ve done that.”

HHHS president and CEO Carolyn Plummer previously told the Star that doctors in Minden indicated that if the Haliburton ED were to close as a result of a physician shortage, “It would not be safe for that one Minden ED physician to provide coverage for the entire County — which meant that the Minden ED would also have to close, leaving Haliburton County with no local services.”

The plan now is to increase the number of ED spaces in Haliburton to 15 from the current nine and grow the waiting room to space for 27, up from 14. Lab space and parking are also being expanded.

While these changes may look good on paper, Carter doesn’t buy it.

He points out that the Minden ED isn’t meant to be a full-service hospital, but rather, a place that can treat and release patients with a variety of conditions, and stabilize more serious cases and keep them alive while doctors determine where they need to be sent for further investigation and treatment. He likens the Minden ED model to that of the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in the TV show “M*A*S*H.”

“The U.S. Army tried to put treatment centres close to the battlefront so that they could treat people quickly after they’ve had a trauma so they had a much better chance of long-term survival,” Carter says. “The same thing is true of emergency departments. They need to be close to where the trauma is.”

The Minden ED is situated right along the Highway 35 corridor, a major trucking and tourism artery, making it an ideal place to deal with car accident victims who may need to be sent to larger centres for care, Carter notes. There is an Ornge Air Ambulance landing pad that can take patients to trauma centres in Toronto.

“You need to get people as close to the scene or the time of their trauma to be able to treat them if you want to have a good chance of success,” Carter says.

As for local EMS, he notes the county government has been left with the task of figuring out how many more paramedics might be needed.

“It’s going to cost us more money and we’re going to get less service,” he says.

Minden ED seen as a lifesaver

At the Gathering Place, a community drop-in centre run by the Anglican Church on Minden’s main drag, there is only one topic on everyone’s lips.

Richard Bradley is there. So is his wife, Sandra Bradley.

Like many, she believes she might not be here today were it not for the Minden ED. About 15 years ago, Sandra was at her cottage with friends when suddenly she “just didn’t feel right.” Then came the triple vision, vertigo and nausea. Her friends looked up the symptoms online and called 911. Her friends drove her to the ED, where Dr. Doug Fiddler diagnosed a stroke. Fiddler put her in an ambulance and rushed her to Ross Memorial Hospital in Lindsay, where she made a near-recovery.

“I may not have the ability to do the many things I do now had the Minden ED not been there,” she says.

“In that golden hour,” chips in Richard, “they did what they had to do.”

Last month, the Bradleys launched a bid to halt the closure by submitting a complaint to the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario. Sandra, who suffers from chronic pain, was seeking a moratorium on the closure and $1 million — an amount she believes to be the value of her life if she were to die due to an “unreasonable delay in being transported” to the next closest ED in Haliburton. Despite the closure, the couple say they intend to see the complaint through.

Wendy Ladurantaye, who volunteers at the Gathering Place after retiring last year from a local college, says she’s lost all trust in the board of HHHS, especially over its insistence that the near-closures in Haliburton somehow affect Minden’s ED, which was pretty much fully staffed through to September.

“It wasn’t Minden,” she says. “It was Haliburton. They twist things.”

Just south of town on Spring Valley Road, Jennifer Semach tends to her horses and laments that with the closing of the ED, charities like hers, as well as local businesses, might not make it. Semach runs Walkabout Farm Therapeutic Riding Association, a charity that provides therapeutic riding and equine-assisted learning for differently abled children and adults with complex physical and mental health needs.

Semach and her husband bought the property five years ago for the farm specifically because of its proximity to the Minden ED.

“Many of our program participants require around-the-clock care and they need to know that emergency services are nearby,” she says, stroking the chin of Gracie, one of nine horses on the farm. “We’ve already had two families who have children with fragile medical conditions who were forced to cancel because they knew the Minden ED was closing.”

Semach says she worries this is just the beginning of what could become an avoidance of Minden because of limited medical care, a situation that could deeply impact local businesses, too.

“Speaking with several local businesses both in the not-for-profit sector and for-profit sector, we are all concerned this closure is going to impact opportunities for programming, growth and of course tourism,” she says. “I’m just so sad for the people that we serve here at our organization because now it’s one more barrier being thrust before them to be a part of the community when they’re already so marginalized.”

Carter notes there is no doubt the closure will have a detrimental impact on many of Minden’s residents, the majority of which are over 50.

“We have one of the oldest communities in Ontario, so we have lots of people who just don’t have the wherewithal to easily travel the extra 20 minutes to get to the hospital in Haliburton,” he says. “They may not have a car, they may not have money for gas, and we only have one taxi in the whole area. Unfortunately you can’t schedule emergencies. The need is immense.”

Ontario ERs are struggling

Porzuczek, organizer of Wednesday night’s vigil and a spokesperson for the “Save Minden ER” campaign, says he intends to take the lessons learned to continue to push for a return of the ED while also reaching out to other rural communities whose emergency departments might be under threat.

Indeed some public-health activists fear what is happening in Minden is a portent of things to come across the province. Local health boards and the provincial government are struggling to fill shifts in smaller hospitals hit hard by post-COVID attrition due to burnout and the prospect of better wages in bigger centres.

A recent Star analysis found 24 EDs serving primarily rural areas of the province were forced to close more than 150 times between February 2022 and February 2023, representing a collective 4,430 hours when the emergency care needs of local residents could not be met.

The spectre of further permanent closures of emergency departments across Ontario is real, says Brenda Scott, co-chair of the Chesley Hospital Community Support committee, which has begun to contact other small communities with EDs, such as Wingham, Walkerton, Clinton and Seaforth.

Last week, Porzuczek and a small delegation from the Save Minden ER group travelled to Chesley, Ont., in Bruce County, to network with the Chesley committee, another grassroots group that has watched several nearby EDs struggle to stay open.

Chesley’s ED was forced to close 30 times in just over the past year; it is now fully closed on weekends and operates from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m. on weekdays only. Between October and December of last year, it was closed for eight weeks.

“If it can happen here, it can happen anywhere,” Scott says. “We’re just one of many small, rural hospitals in Ontario.”

Hannah Jensen, a spokesperson for the health minister, says the province has made efforts to bolster Ontario’s health-care workforce through various programs. Those include the Learn and Stay grant, which provides eligible nursing students, among others, with upfront funding for tuition, books and other costs in return for those students staying and working in the region where they studied for a specified term; expanded “As of Right” rules, allowing health-care workers registered in other provinces and territories to immediately start working in Ontario; and working with health regulatory colleges to help internationally educated workers become licensed here.

On Thursday, the province announced that it is extending to the end of September its Temporary Summer Locum Program, created during the pandemic to connect doctors with rural and northern EDs. The program allows doctors to claim premiums for working in rural and northern EDs and covers certain travel expenses.

Jensen added that the province’s Emergency Department Locum Program, which provides doctors to hospitals facing challenges with staffing emergency department shifts, averted nearly 1,500 ED closures last year.

“As always, our government will continue to work with any hospitals who want to utilize any of these programs.”

And in what could be a temporary respite for some Minden residents, the Kawartha North Family Health Team this past week submitted an expression of interest to Ontario Health to receive funding for an Urgent Care Clinic at the Minden hospital.

“We are aware that ideally, the site would continue to operate as an Emergency Department; unfortunately, this is not a service we are able to apply for or deliver,” said health team executive director Marina Hodson in a statement Wednesday.

“In light of this, we felt strongly that this option would provide the best opportunity to continue to have health care services locally for the residents of Minden Hills. As a resident of Minden Hills, myself, I realize the limitations of our resources and how stretched Healthcare providers are, especially during the busy summer season, and we hope that if this proposal is approved, we would be able to alleviate some of this burden.”

While Richard Bradley acknowledges that something is better than nothing, he stresses that this is not what the 25,000 community members who signed the petition for a moratorium were asking for.

“Basically now you have to schedule your injury,” he says, noting that the helipad will remain closed. “If they want to do that for the summer and bring back our ER docs in September, we’re fine with that. But we still want our ER doctors back.”

Minden’s last shift

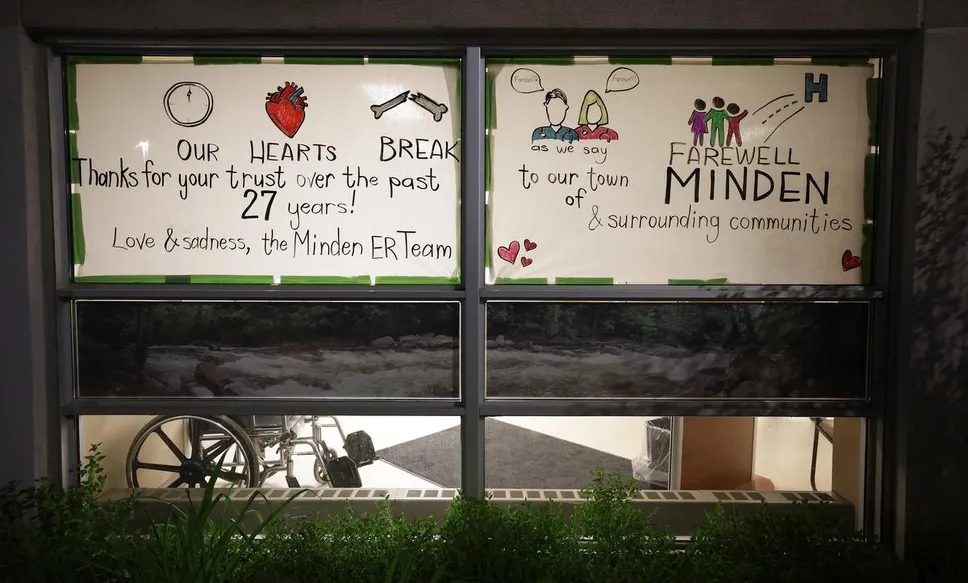

Back at the Minden ED on Wednesday, it’s about midnight and staff on the last shift pass a poster written on bedsheets and erected at the main doors — “Our hearts break as we say farewell to our town of Minden & surrounding communities. Thanks for your trust over the past 27 years! Love & sadness, the Minden ER Team.” Then they walk into the arms of grateful community members who stayed to the end.

There are hugs, a few tears and even laughter. Staff spend several minutes reading every thank-you and farewell card from community members left on the doors.

“There’s a lot of history here, and I’m so thankful for what they were able to do and what they were able to create for the community with this hospital,” says Porzuczek. “They created a hospital that in my eyes is almost like having a mother. So whenever you’re hurt, whenever you’re sick, you always rely on your mother. So this is where you came to. They were the guardians of the community.”