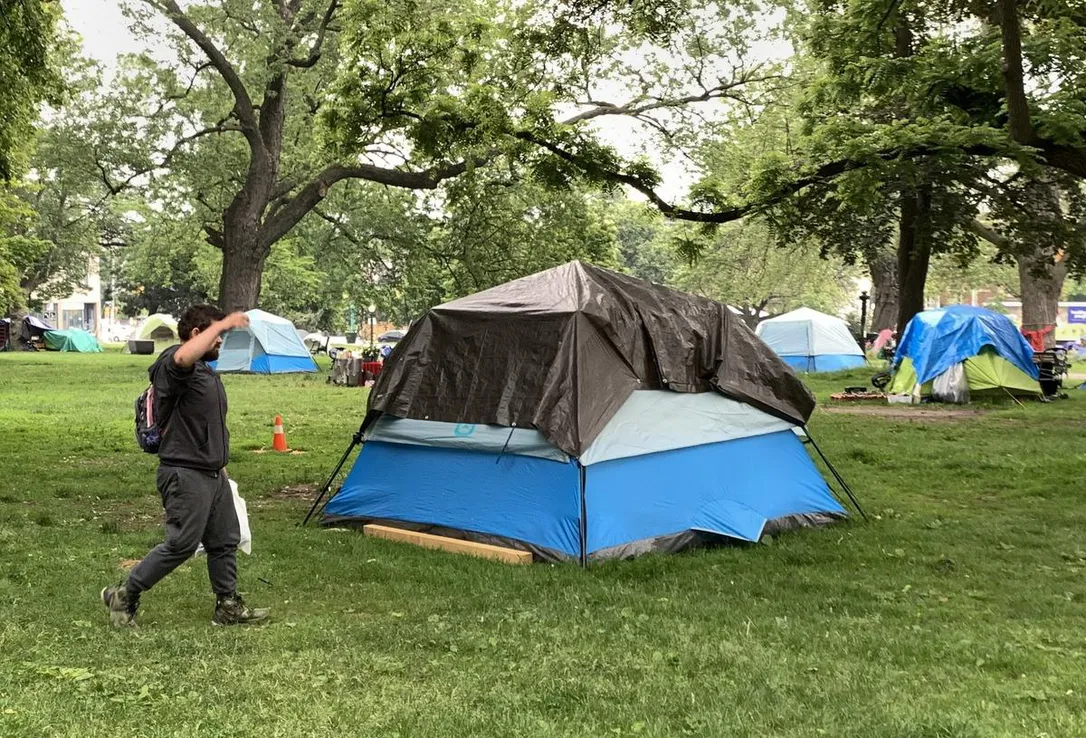

The number of homeless encampments in Toronto is once again on the rise, after falling last year to a quarter of their footprint during the pandemic.

With twice as many camps this May as there were a year prior, it represents another symptom of the city’s deepening homelessness crisis.

According to new data provided by the city, the most prominent clusters are on the east side of downtown, including 45 tents and structures in Allan Gardens, and numerous camps in the Lower Don Parklands and Riverdale Park. Across Toronto, as of mid-May, city staff were aware of 199 camp setups spread over 90 locations.

That’s a dramatic jump from the same time last year, when staff knew of 105 tents and structures — 88 on parks and recreation land and 17 in locations overseen by the city’s transportation department — though it’s still well below the roughly 400 structures seen in mid-2021.

The rise corresponds with system-wide pressures: there are simply more people homeless in Toronto this year than last, and for several months the number of people turned away from shelters has been rising. City hall, meanwhile, expects to shut down two of its pandemic-era shelters by late summer, at a time when funding to hand out new housing subsidies has run dry.

To Lorraine Lam, an outreach worker in the downtown east, the surge doesn’t come as a surprise, given the rising toll of homelessness across the city.

“As someone who has done this work for so long, I feel like this is totally predicted and anticipated,” she said.

Rising numbers

Across Toronto, more than 10,500 people are known to be homeless, according to the city’s latest data from April — six per cent more than the count one year earlier. In the same month, an average of 143.7 people per day were turned away from shelters for lack of space.

The latest citywide street survey, from spring 2021, indicates that most people weathering homelessness outside are men, at 80 per cent; a disproportionate 23 per cent are Indigenous. The average age was 43, and at last count, seven per cent reported being veterans of the Canadian navy, army or air force. Most, at 87 per cent, were chronically homeless.

In interviews with the Star, encampment occupants have cited many reasons for turning to life outside, though many have cited fear of theft or violence in shelters. In recent years, there has been a sharp increase in documented violent incidents in Toronto’s homeless shelters, attributed to crowding, inadequate mental health supports and the opioid crisis.

Toronto physician Andrew Boozary, who works with patients facing homelessness, says he’s seen people make the “impossible choice” to stay outside due to both safety concerns and difficulty in finding beds. He worries that, without more housing options, people surviving outdoors will face long-term health effects — from sleep disruption to the effect of heat spells or air pollution from wildfire smoke, which could worsen conditions like asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chronic issues could become acute or even fatal, he said.

“This is why it’s a real public health concern.”

Visible versus invisible

While outdoor homelessness existed in Toronto before COVID-19, the pandemic thrust it into the public eye, as camps cropped up in areas where they hadn’t typically been seen, such as Trinity Bellwoods Park.

After a series of high-profile encampment clearings in 2021, people seemed to retreat from visible locations. Last summer, while there were still camps in Grange Park and Allan Gardens, there were fewer tents overall, and the most common location was the Lower Don Parklands — dense woods, cut through by walking and biking trails, along the edge of the Don River.

This year, as the number of known camps has again surged, they’re spread across the city, from Scarborough City Centre to the Humber Arboretum and Trinity Square, though several of the most common spots are in the downtown east, including roughly a quarter in Allan Gardens.

Lam said that for some, a decision to move to a more visible park encampment such as Allan Gardens can be about access to services.

She sees the camps clustered in the downtown east as reflective of the area’s historic role as a hub of social services in Toronto. “These were the pockets of neighbourhood where people gathered for health care, for mental health resources, for food security,” she said.

In recent years, she said, the city has also created priority programs to move people from high-visibility locations such as Dufferin Grove into hotel shelters or housing.

“I think there are people in the system who also know that the more visible you are, the more likely you are to get services,” she said. “Everybody just wants a chance to get housed.”

It is harder for those who live more off the grid, Lam observed. She recently spoke with one man who showed her a yellowing copy of his 2010 application for subsidized housing. After probing his case, Lam learned a home fitting his needs had become available in 2016, but as he was living transiently, officials couldn’t get in touch. His application was then cancelled.

“Now we’re going to have to start all over again.”

‘This is only going to get worse’

To both Boozary and Lam, the outlook is bleak.

“This is only going to get worse in the months to come, from what we’ve seen,” Boozary said, citing the city’s mounting struggles with shelter capacity, the end-of-August closure of two shelters that house roughly 350 people, and a plan to squeeze more beds into existing sites.

There are fewer exit routes now, too, with city hall burning through a year’s worth of funding for portable housing subsidies — meant to last until spring 2024 — by the end of last month.

At city hall, officials have been raising alarm bells in recent months. In April, the head of the city’s shelter department, Gord Tanner, warned that Toronto is spending $317 million more than it has budgeted for shelters this year. Without extra funding from other governments, he warned Toronto could have to fast-track the ongoing shelter closures as early as the beginning of 2024.

Last week, Deputy Mayor Jennifer McKelvie announced the city would begin redirecting refugees who turned up at city shelters to federally funded sites instead, which she framed as a difficult decision to create more space. At the same time, the city would be reducing the distance between beds — extended during the pandemic — back to pre-COVID levels.

When asked about the rise in encampments, McKelvie pointed to a set of recommendations from Toronto’s ombudsman, Kwame Addo, that were recently accepted by city council. Addo’s report said that, if the city decided it was necessary to clear a camp, it should ensure it met certain parameters, such as providing mental health services at the time of the clearing.

While stressing the city was prioritizing a “humanitarian” approach with those camping outside, McKelvie also told reporters that city staff had her support “in enforcing the rules.”

Lam, all the while, is urging the city to focus on creating affordable housing to give people a way out of homelessness — lest people simply be displaced from one encampment to another.

“Everybody that I’m working with, they’re just trying to survive.”